Simulating auditory lexical decision using DIANA

This project is done in collaboration with Benjamin V. Tucker and Louis ten Bosch.

Computational models of spoken word recognition attempt to both describe and simulate the process of spoken word recognition. Usually, the performance of these models is compared against the performance of human listeners in behavioral tasks. We used an end-to-end model of spoken word recognition called DIANA to simulate participant behavior in an auditory lexical decision task and test whether DIANA’s performance matches human performance.

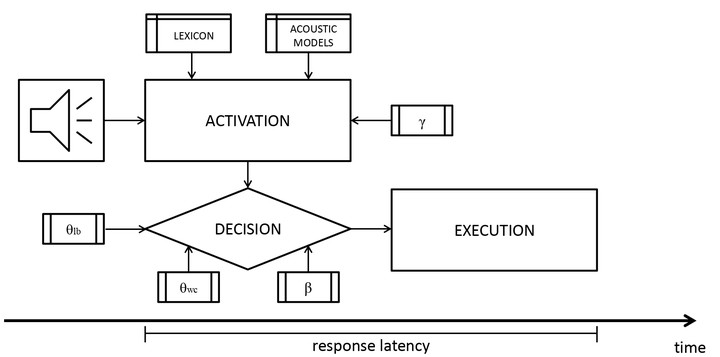

As can be seen in the figure above, DIANA takes actual sound as input. It calculates the activation of different candidates (for example, words) depending on its acoustic models, what exists in its “mental” lexicon, and some preconceptions about what is expected to be heared (for example, higher frequency words are given higher activation; this is controlled by the gamma parameter you see in the image). As it calculates activation, DIANA also makes decisions, and this process is governed through a few weights and thresholds applied to the activation values. Finally, when a decision is reached, DIANA executes this decision in a simulation of a button press.

This architecture enables us to generate model estimates of response latency and accuracy and compare them to decisions that human listeners make. We tested exactly that by comparing DIANA estimates to human data from the Massive Auditory Lexical Decision project, while presenting DIANA with the same word recordings that the human subjects heard.

We first created new acoustic models for DIANA to use and tested its ability to recognize words from the input signal. DIANA’s accuracy was close to 90% in accurately recognizing almost 5,000 different words from a list of 26,000 words in its lexicon. Even when it made a mistake, the candidates were sensible and the actual word was very frequently in the top ten candidates. For example, The word proceed was recognized as precede, but proceed was the runner-up. Other close candidates were preceded, perceived, proceeding, preceding, poppyseed, airspeed, proceedings, preseason, and concede. Make sense, right?

DIANA also performed fairly well when it comes to deciding whether the input signal is a word or not. We tested different threshold and parameter values and at all times relied on MALD data to have DIANA perform similarly to actual participants (not spamming the “word” response only, for example). Under one possible setup, DIANA made 56% of “word” responses with an accuracy of 88% when responding to words and 76% when responding to pseudowords. In this case, it performed better than a quarter of MALD participants when responding to words, but the pseudoword accuracy was lower than most MALD participants, so there is room for technical improvement.

When it comes to estimating response latency, the results were heavily influenced by word-recording length. Simply put, the estimated response latency DIANA produces can be almost entirely replaced by the duration of the signal when predicting MALD participant response latency. To be fair, recording duration is the best predictor of response latency in statistical analyses of the auditory lexical decision task data, but not to this extent. Our simulations showed no impact of word frequency (which is a recorded effect in behavioral tasks). Additionally, DIANA and human participants showed an opposite trend when it comes to deciding about the winner past signal offset, if the decision hadn’t been made before that: DIANA added more time for decision-making for longer words, while behavioral data shows that participants make a decision faster than when short words are presented.

To summarize the main points of our project, DIANA can take actual acoustic signal as input and provide explicit estimates of response accuracy and latency, allowing comparability to behavioral data. Our implementation of DIANA successfully recognized nearly 90% of words between approximatelly 25 thousand candidates in the lexicon. The model also performs fairly well in deciding whether an input signal is a word or not, and it is predictive of human response latency in the behavioral task. However, most of that predictive power comes from the fact that both DIANA and the human participants are listening to the same recordings, so recording duration plays the crucial role. The current implementation of the decision time past word offset does not align with behavioral data, so some conceptual adjustments may be needed in the future. A lot more detail is presented in a freely available paper we published, with the supplementary material available online. If you’re interested, you should also look at this publication about DIANA by Louis ten Bosch, Lou Boves, and Mirjam Ernestus.