Relative entropy in spoken Romanian verbs

This research was completed in collaboration with Petar Milin and Benjamin V. Tucker.

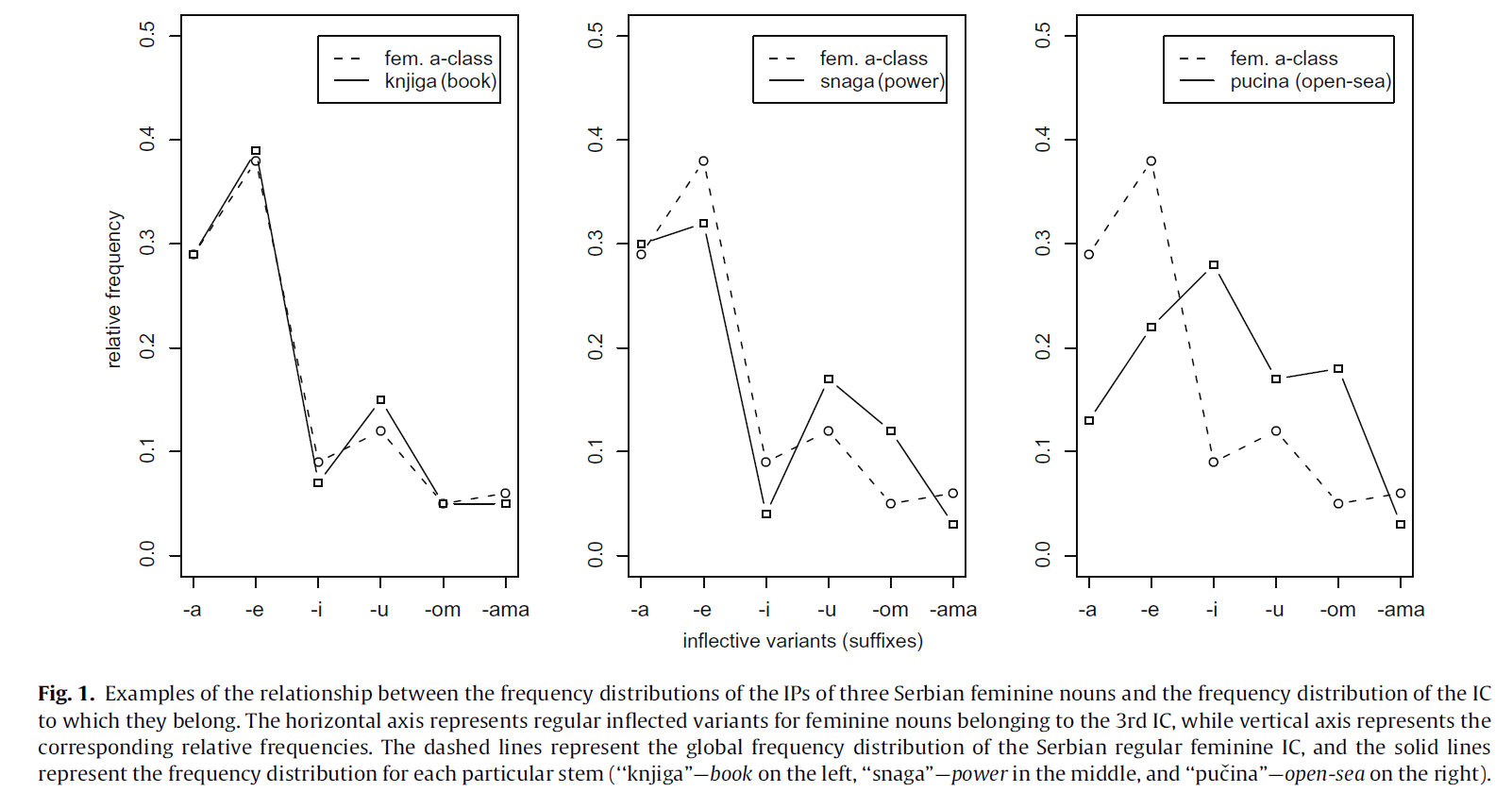

In certain languages, new forms of a word with slightly different meanings can be created by adding one of the standard set of so-called inflectional suffixes used in that language. For example, the verb work can be made to fit a third person by adding an inflectional suffix -s to make he/she/it works. Some languages use this tool to create different forms of words profusely. In the image below, taken from Milin et al. (2009), you can see that in Serbian seven different suffixes presented on the x-axis can be attached to the base of the feminine noun book to create new word forms (e.g., knjigom means with the book). Words that follow the same process of inflection are then said to belong to the same inflectional class. In the example below, book has a distribution of relative frequencies of its word-forms that is nearly identical to the one of the entire class it belongs to (feminine a-class). In turn, the Serbian word meaning open-sea shows a substantial lack of alignment to the class. This lack of alignment is measured in terms of relative entropy (hence the name). Studies show that words with a word-form frequency distribution more similar to the word-form frequency of their entire class are processed faster. In other words, it is easier to deal with words like book which show a word-form frequency pattern like most words in their class, than with words like open-sea.

These findings come primarily from visual lexical decision studies. In these studies, the participants are presented with written words and made-up strings of letters. Their task is to decide whether something is a word or not as quickly and as accurately as possible. However, spoken word recognition and reading are not quite one and the same. For example, the acoustic signal unfolds in time, while a single word (or a non-word string of letters) can be glimpsed in a single look. Additionally, one can always have another look at a written word, but we cannot “turn back time” and replay something that had already been uttered. For those and other reasons I do not mention here, we decided to test whether the relative entropy effect can be replicated in an auditory lexical decision task. That is, we presented our participants with audio recordings of words and non-words, rather than written words and strings of letters with no meaning. We also tested the effect in a new language (Romanian) and used verbs and their different forms, rather than nouns as in the example above. The effect of relative entropy in verbs was already recorded in a previous study, but in Serbian and with written words ( Filipović-Đurđević & Gatarić, 2018).

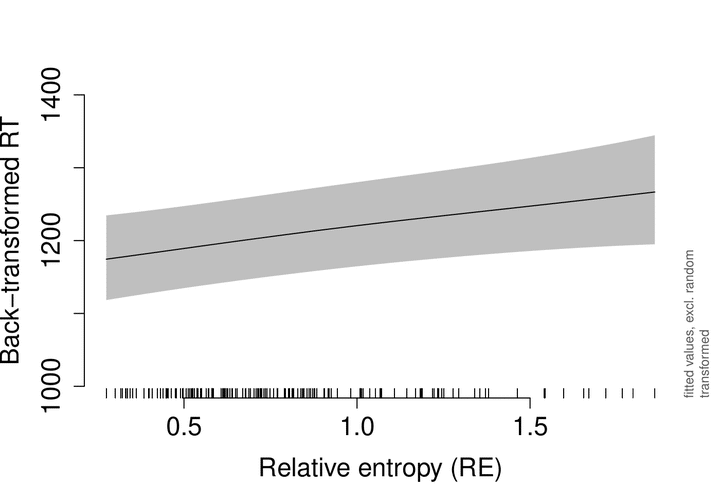

Our results also captured the relative entropy effect, as can be seen in the figure at the top of this page. The figure shows the effect for the time it takes participants to recognize whether the sound recording is a word of Romanian, but we found a similar effect for participant accuracy. If a verb has a distribution of relative frequencies of its forms that is much different than the class it belongs to, listeners make more errors (they are more prone to say that it is not a word) or they respond to the verb more slowly. These findings are important because they inform us that speakers of a language are sensitive to patterns found in the language and that they learn these patterns and adjust their language processing accordingly. The purpose of mentally storing information about some statistical regularities in language is to enable faster decision making and to make decisions in cases of uncertainty more likely to be accurate. Much more detail and topics I do not mention in this brief overview can be found in our research article.